It’s no secret that I love genealogy. I often say if I wasn’t a writer, I would have been a professional genealogist. The excitement of the chase and the thrill of finally finding that piece of evidence that proves a relationship would enthrall any mystery lover.

And it’s not just my family I enjoy researching. I will jump in and help anyone trying to solve a brick wall. Most genealogy buffs seem to share this insatiable urge to research, as evidenced by how willing people are to help others in many online groups.

Tonight I get to share some of the passion I have for genealogy with the South Jersey Writers Group. I’ll be talking about how my family history habit has crept into my writing, in the areas of character development and worldbuilding.

I’m a bit nervous about presenting, but I am eager to share with this group. I’ve met some of these writers in other venues, and they are always warm and fun. I’m looking forward to a good discussion with them.

Do you have a hobby that invades your writing?

Philadelphia Writers’ Conference 2018: My Biggest Takeaway

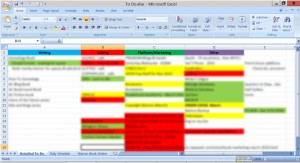

I’m not talking about plot complexity. Even the simplest story is complex in the way I mean. What I mean is how every element of your story impacts the others. In our character workshops, we also crossed into plot. In our plot workshop we also delved into character. Every word choice and point of view feeds into the elusive element of voice. Everything interconnects, playing off each other and driving the story in different ways.

That same complex interconnection often makes revision a mind-bending project. Change one thing about a character, that can change the plot. Change POV, and your voice skews. Change the language and that might suggest a change in structure. Every change, no matter how minor, flows downstream all the way to the end of the novel. Riding those rapids can exhaust you.

This complexity of story comes from the fact that stories reflect the complexity of life. This helps stories translate across different media. The same story can be told orally, in print, in graphic novels, or on a screen large or small. Although the formats differ, the story fabric can be cut and tailored to each one to convey the same meaning and soul as the original story. The interwoven complexity of story gives it both strength and malleability.

Given the complex nature of writing and all its elements, is it any wonder that the craft of writing is so hard? The work of weaving a tale can take an emotional, psychological, and even physical toll on writers. To combat this, we need connectivity of our own—a network of friends and supporters who understand and can help lift us over the obstacles we encounter. This is one of the values of conferences like the Philadelphia Writers’ Conference. There we meet and connect with other writers and form bonds that last.

Thank you, PWC, for 70 years of helping writers connect so we can weave our stories together.