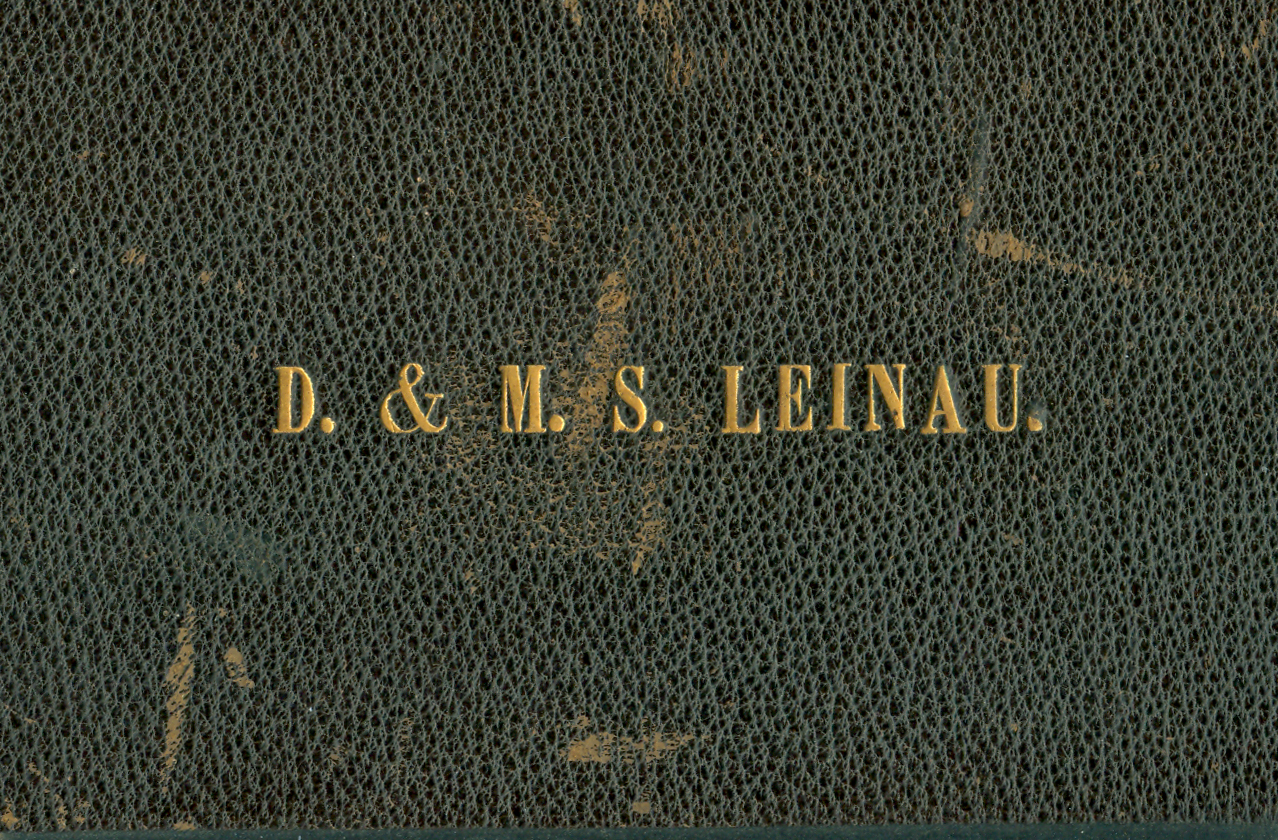

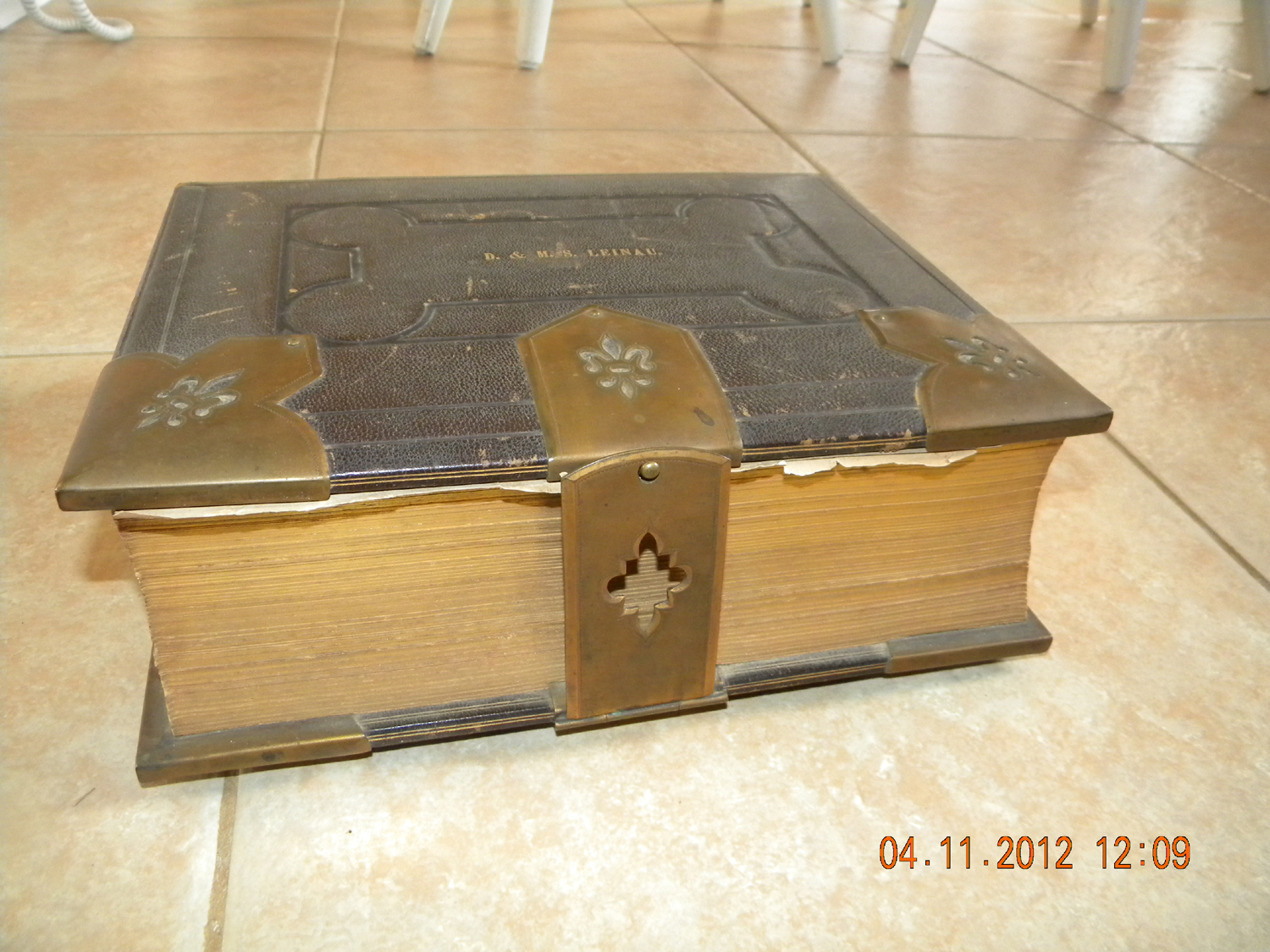

This weekend, I came into possession of my grandfather’s sketchbook. Grandfather Gans died when I was four, so I have no memory of him—just “memories” generated by photographs and a stuffed bunny that he (and my grandmother) gave me for my first Easter.

Three of my grandparents died before I was old enough to remember them, and unfortunately the fourth was ill for some time before she died, so I never knew the real her. In all the most important ways, I never knew any of my grandparents. I have always felt the deprivation of this, especially as I have grown older and become more and more interested in family history.

Getting this portfolio had an unexpected effect on me: I felt like I knew something of my grandfather for the first time. Art is so emotive, so expressive of the artist, that something of the person remains long after they are gone. What my grandfather chose to draw, and the style in which he drew it, gave me a peek into his mind and soul.

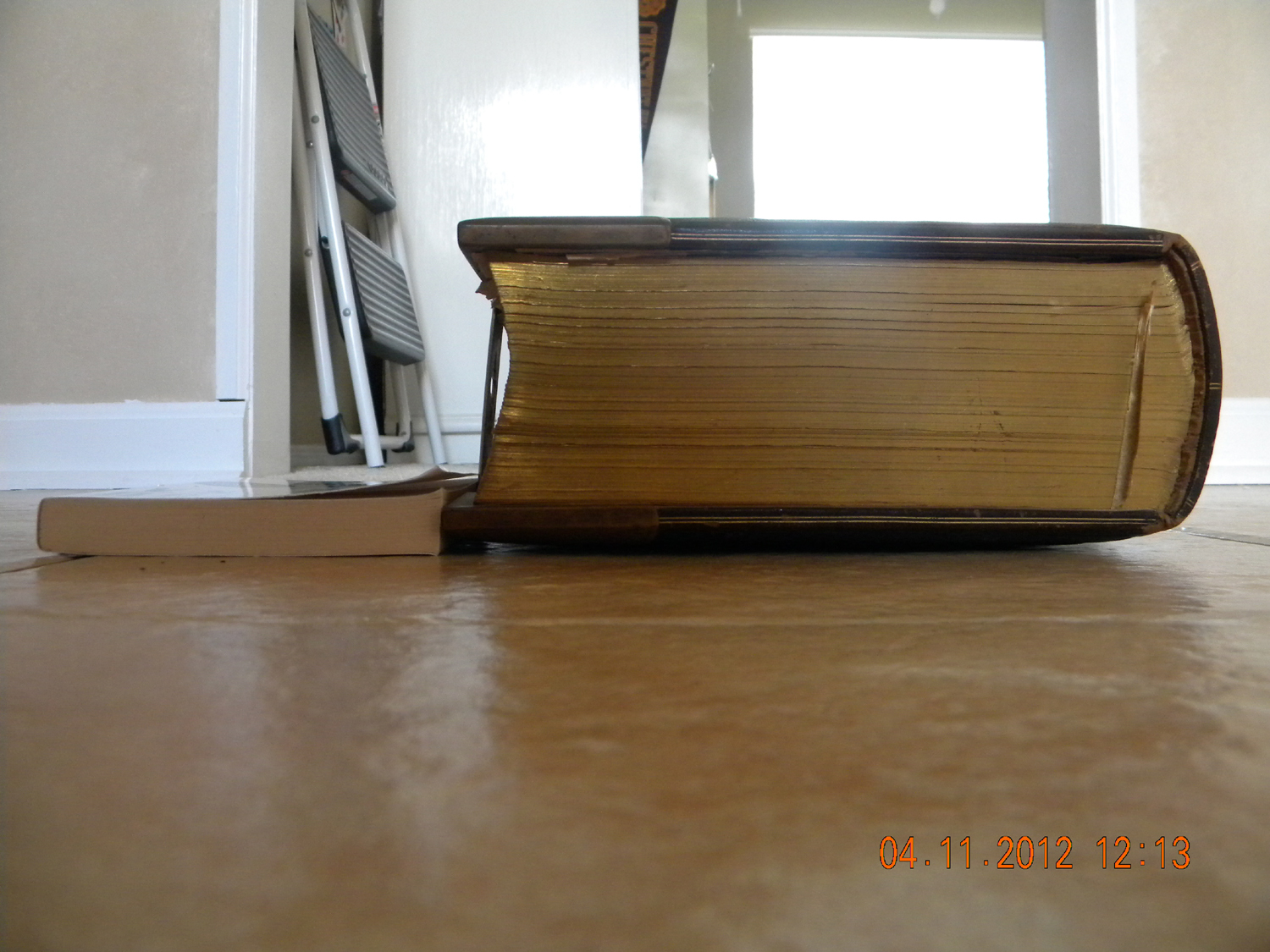

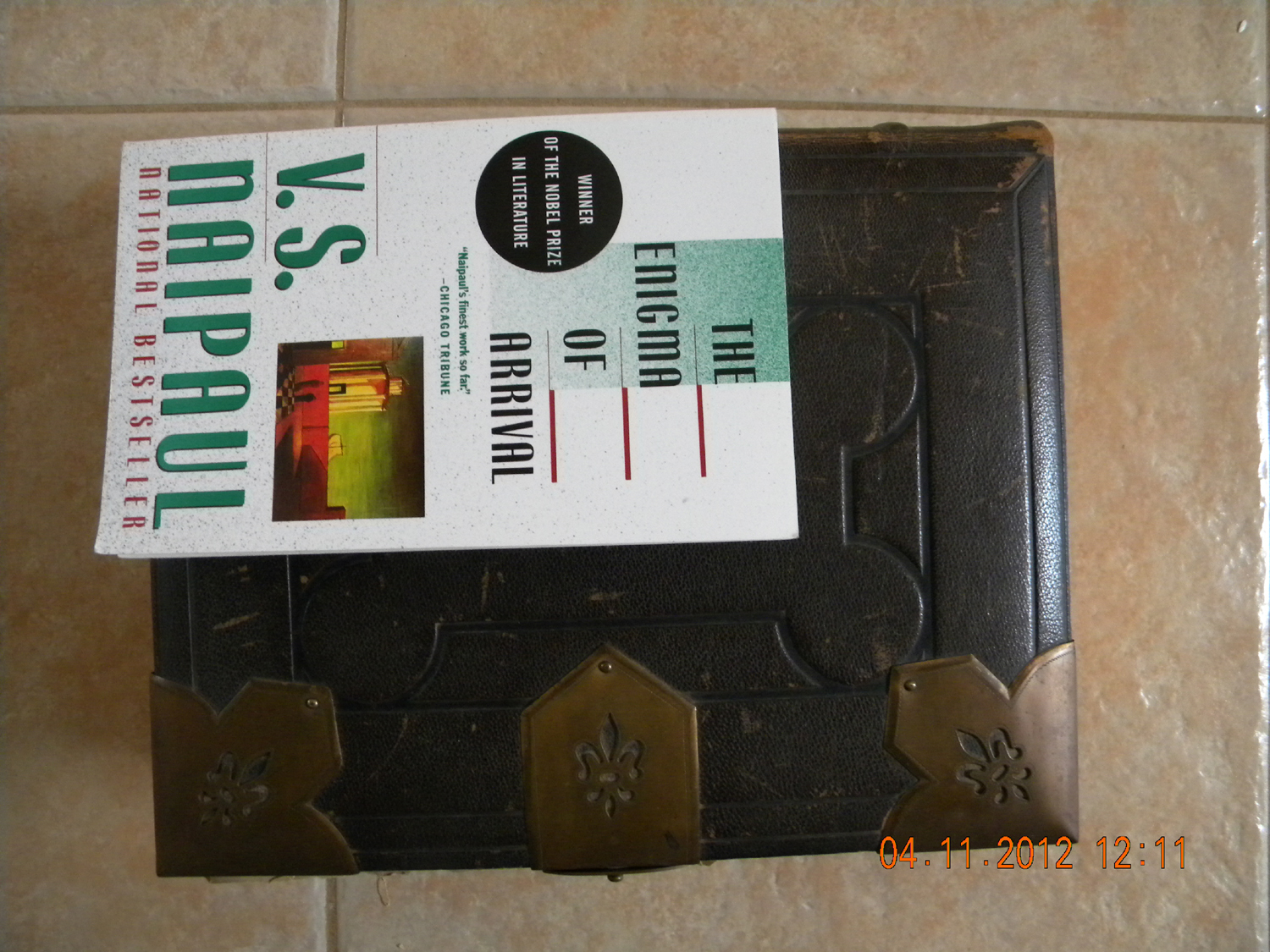

He drew people:

And scenes:

And ships:

And cartoons:

The style of my grandfather’s drawings are very much like my father’s drawing style. The similarity is rather spooky. The precision of line, the attention to detail, the choice of materials, even the subject matter was all eerily familiar. My grandfather came alive as he never had before.

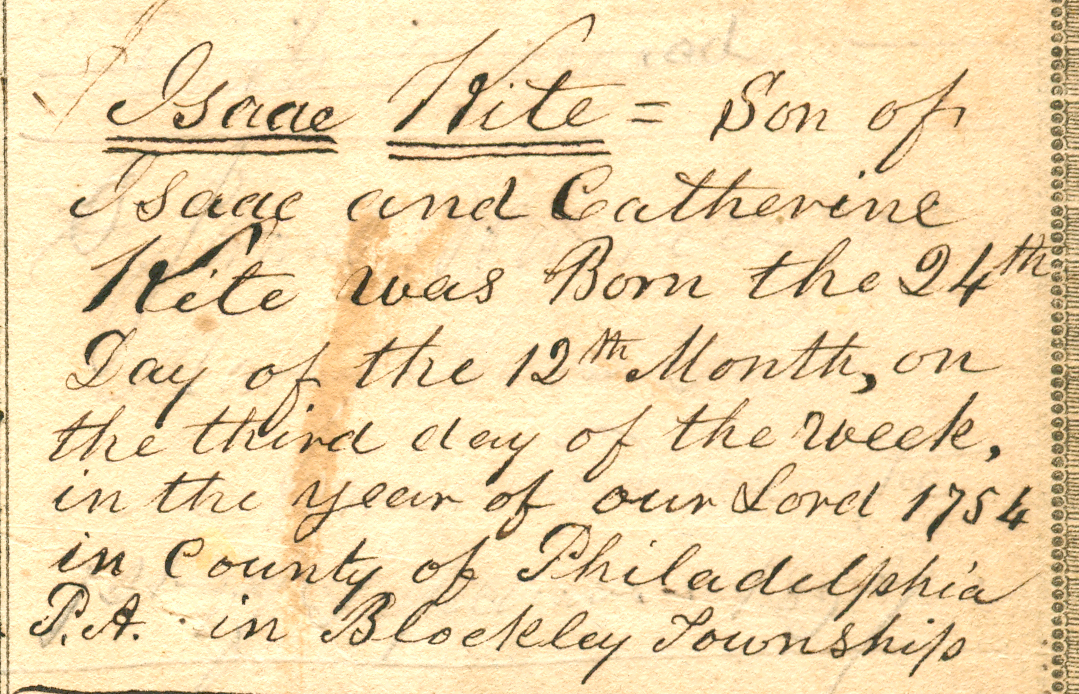

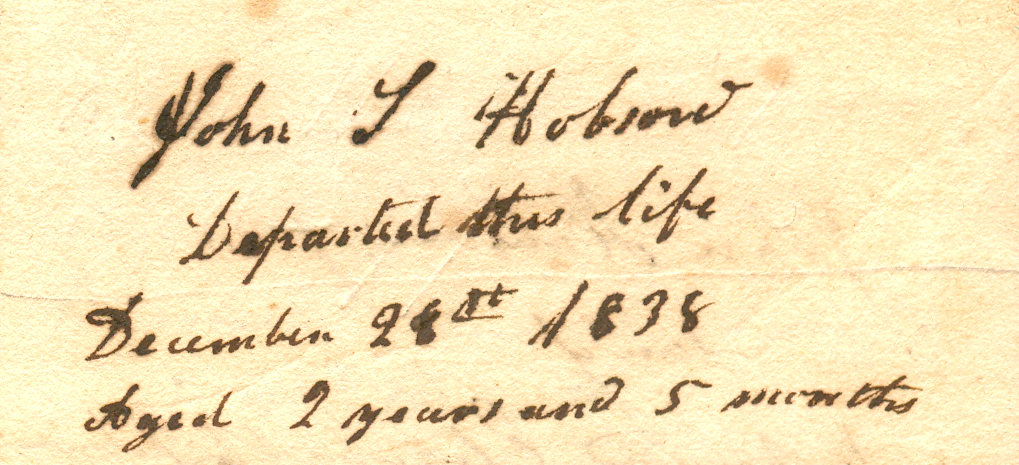

But among all his wonderful drawings, a small slip of paper, only about half a finger long and a finger wide, spoke most loudly to me. On it was his careful calligraphy:

The name of his wife. Saved for 75 years.

For the first time, I touched my grandfather.